Why Do Children Born to Teenage Mothers Have Worse Lifetime Outcomes?

Children born to teenage mothers have worse outcomes—poorer health, less schooling, and lower earnings in adulthood. However, the cause of the worse outcomes is not clear. Do these children have worse outcomes because of teen childbearing or because mothers who have teen births come from more disadvantaged backgrounds, so their children are likely to have poorer outcomes irrespective of the age of their mother at birth? Anna Aizer, Paul Devereux, and Kjell Salvanes disentangle these issues and examine the outcomes of children born to teens.

They explore the impact of teen motherhood on children’s short-, medium-, and long-term outcomes. To address the fact that teen mothers usually come from disadvantaged backgrounds, they construct a study of the children of pairs of sisters. Using a Norwegian data set that links individuals across three generations, they compare the outcomes of children born to a teen mother with the outcomes of the children of her non-teen-mother sister.

Limiting their analysis to a sister comparison controls for differences in family background, and the estimated effects of teen childbearing on offspring outcomes decline considerably, but the team still finds a negative relationship relative to the outcomes of cousins born to non-teen moms.

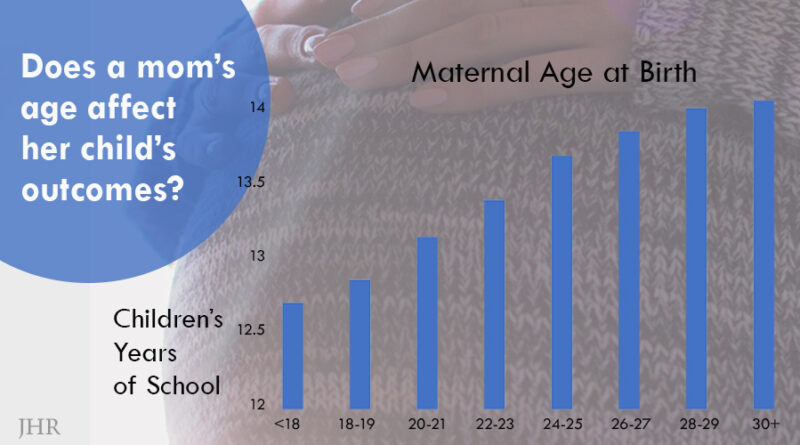

Children born to teen mothers have cognitive test scores that are 13 percent of a standard deviation lower. They complete half a year less schooling. By age 30, they have 4 percent lower earnings. And they are three percentage points more likely to have a teen birth themselves.

Two factors explain most of these effects: lower levels of schooling of the fathers and fewer household resources when the child is growing up. Interestingly, there is no sharp improvement in outcomes when mothers turn 20. Rather, offspring outcomes improve continuously with the age of the mother until she reaches her mid-twenties.

Many programs and policies have sought to reduce the teen birth rate. According to the authors, two policy implications follow from this analysis. “First, programs that target young first-time mothers should also consider providing services to the fathers. Second, while policymakers are right to focus on births to the youngest mothers, delaying childbearing until at least age 24 may be optimal.”

Read the study in the Journal of Human Resources: “Grandparents, Moms, or Dads? Why Children of Teen Mothers Do Worse in Life,” by Anna Aizer, Paul Devereux, and Kjell Salvanes.

****

Anna Aizer is at Brown University and NBER. Paul J. Devereux is at School of Economics and Geary Institute, University College Dublin, NHH, CEPR, and IZA. Kjell G. Salvanes, Norwegian School of Economics, CEPR, HCEO, and IZA.