It’s University Press Week! We’ve just launched our blog, and we’re excited to be participating in the UP Week Blog Tour, where presses will be blogging each day about a different theme that relates to scholarly publishing. For the full Blog Tour schedule, click here.

For today’s theme of The Global Reach of University Presses, Sheila Leary, director of the University of Wisconsin Press, interviews Jan Vansina.

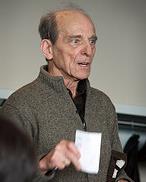

Jan Vansina, one of the world’s foremost historians of Africa who literally wrote the book on using Oral Tradition as History, is about to publish his eighth book with the University of Wisconsin Press. He recently had occasion to look back at how, over nearly fifty years, his seven prior books published by UWP have influenced the study of Africa’s history, both within Africa and around the world.

Jan Vansina, one of the world’s foremost historians of Africa who literally wrote the book on using Oral Tradition as History, is about to publish his eighth book with the University of Wisconsin Press. He recently had occasion to look back at how, over nearly fifty years, his seven prior books published by UWP have influenced the study of Africa’s history, both within Africa and around the world.

“My own case shows that the kind of specialized scholarly books published by university presses typically lead to further research by others and do so for a whole generation or longer. In a field that is new, such as African history was when I began, university presses publish specialized works of scholarship that commercial publishers take no interest in. And I have found that just placing research findings in archives is not enough: publication is absolutely essential to the advancement of research. Indeed, I would argue that university presses are as essential for research in the humanities and social sciences around the globe as are laboratories for research scientists.”

Vansina is considered one of the founders of the field of African history in the 1950s and 1960s, a time not so long ago when there was still a widely held view that cultures without written texts had no history, or that their history was unknowable. Up to that point, “African” historiography focused entirely on the history of European colonizers in Africa, not on the history of Africans.

As a young employee of a Belgian research agency sent to the Congo in 1952, Vansina discovered that he could analyze the oral tradition stories he heard from Kuba informants by using the same methods he had learned for extracting historical information from European medieval dirges. This was a historiographical breakthrough that gave the study of pre-colonial African history both the scholarly justification and the self-confidence it had been lacking.

Vansina recalls the impact of his first book with UW Press in 1966, Kingdoms of the Savanna.

“It was a preliminary historical overview of an area and period in Africa that was little known in academic circles at that point. It was quickly translated into French and published in Kinshasa, and it won the Herskovits Prize for best book from the African Studies Association.” Although historians at the time were accustomed to studying kingdoms, the book used a very innovative mix of oral and written sources to provide a history of pre-colonial kingdoms in central Africa.

“Over the next twenty-five years or so,” Vansina remembers, “several scholars were inspired by the book to pursue their own research in the past of the various kingdoms I wrote about, so that by the year 2000 individual monographs had been written about nearly all the major kingdoms of the southern savannas (at least five in RD Congo, three in Zambia, and three in Angola).

The impact of Kingdoms outside academia was rather colorful, Vansina recalls. “In Central Africa many in the Congo read it, and it became coveted underground reading for those in the Angolan insurrection against their Portuguese overlords. Its popular impact was especially strong in the lower Democratic Republic of Congo (or RD Congo), where local demand has been strong enough to produce a translation in Kikongo around 1990 and another one in Lingala. In the 1970s there was even a local church calling itself ‘The Church of the Kingdoms of the Savanna.’ ”

In 1978, Vansina published a scholarly monograph, Children of Woot, on the history of a single kingdom in RD Congo. He comments, “The one completely new feature for a history book was the inclusion of its long lexical appendix, as essential to the argument. A monograph like this is not expected to have a host of readers when it is published but it is expected to attract small numbers of researchers for many years thereafter. Thus even today this book and especially its data have not been superseded by anything else.”

Oral Tradition as History, a methodological work published in 1985, is Vansina’s book that is most widely known and used in other scholarly disciplines and area studies beyond African history. “It is a manual about how to handle a certain kind of oral history worldwide, not just in Africa. Some twenty-five years earlier as a young man, what I had written about oral tradition had made a splash and led to extensive debates. This new book was a complete reworking that took into account valid observations made by critics, but still showed the extent to which oral histories of this sort could be relied upon. It has had an active life. For example, just this year it was translated into Indonesian Malay.”

Vansina continued to innovate with his book Paths in the Rainforests (1990), a historical overview built primarily on linguistic and archaeological data reaching more than two thousand years into the past. It attempted a history of the peoples in the Central African rainforests, a large area that had been written off as “without history.”

“But I wrote it as history, introducing new concepts, and included a very large appendix showing the results of comparative linguistic data. No one had ever attempted anything similar, certainly not on that scale, and this book was therefore a bit of a gamble, but it convinced most social anthropologists and archaeologists. I am gratified that from that time onward it has served as an incentive for much further research by others. This year an archaeologist wrote me to say that his discoveries conformed to the predictions the book had made. The most important results of Paths in the Rainforests, though, have been in the field of history, where others have now used similar techniques in their own work, including very deep historical research on the Great Lakes region of East Africa.”

As the field of African history matured, Vansina was one of the first to look back at it in a combination historiography and memoir, 1994’s Living with Africa. That same year, the horrific violence and mass killings in Rwanda returned Vansina’s attention to research he had done in Rwanda from 1957 to 1961. The rich and extensive documentation he had collected was available in an archive there, but no one had made use of it for publications.

“I knew from that research that Rwanda’s past, and historical memories of that past, were quite relevant to a fuller understanding of the genocide and people’s motivations. I also felt that knowledge of Rwanda’s pre-colonial history could contribute to political choices about its future. So, I first wrote a book in French about the main social and political developments of the country, directed as much towards Rwanda’s governing elite as towards historians. But the new elite came mostly from Uganda and used English, not French. So I translated the work into English and UW Press published it as Antecedents to Modern Rwanda in 2004.”

“I knew from that research that Rwanda’s past, and historical memories of that past, were quite relevant to a fuller understanding of the genocide and people’s motivations. I also felt that knowledge of Rwanda’s pre-colonial history could contribute to political choices about its future. So, I first wrote a book in French about the main social and political developments of the country, directed as much towards Rwanda’s governing elite as towards historians. But the new elite came mostly from Uganda and used English, not French. So I translated the work into English and UW Press published it as Antecedents to Modern Rwanda in 2004.”

“Though its narrative and its major interpretations have been accepted by most academics, and also led to the publication of two academic debates about its significance, in Rwanda there is official silence about the book. It has not been formally banned in Rwanda, but the history I present runs counter to the official ideology and now also to the official history the government promulgates. But I know that actually the book has been widely read in Rwanda, even discussed, but no one will publicly admit to this. I hope that it will eventually be recognized and lead to further research in Rwanda.”

Most recently, in 2010, Vansina experimented with another new approach to African history. “Being Colonized: The Kuba Experience in Rural Congo, 1880–1960, was my deliberate attempt to write a book for undergraduates. It presents the history of a colony through the eyes of a colonized people. I used sidebars and illustrations, a format still rather uncommon in works of African history. I resisted reducing the historical complexity of the period to simple formulas. The anecdotal evidence so far has it that while most students like it, many find all those names and the very complexity of the history a bit overwhelming as well. But I hope it will inspire others to experiment further with approaches for undergraduates that will open new perspectives to them.”

Jan Vansina’s legacy also includes an extraordinary impact beyond academia. When the journalist Alex Haley was researching the family history that would become his famous book Roots, a powerful and groundbreaking story of enslaved African Americans, he could find no written documents that directed him to a point of origin in Africa. Eventually, someone suggested that he contact Jan Vansina, who had been doing innovative research on African oral traditions. Vansina suggested that the few words, names, and stories that had been passed down to Haley from an enslaved African ancestor named Kunta Kinte might be from the Mandingo people in Gambia, a culture with a very rich oral tradition recited by trained griots. Eventually Haley’s quest led him to a griot in a remote Gambian village who had memorized the history of a large, extended Kinte family. Two hours into the recitation, the griot mentioned a young man, Kunta, who went away from his village to chop wood and was never seen again. This astonishing connection was the beginning of a great movement of reclamation of African heritage by African Americans.

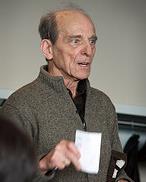

Jan Vansina. Photo by Catherine A. Reiland / African Studies Program, UW-Madison. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Now 84 years old and professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Jan Vansina was an early recipient of the “Distinguished Africanist” award by the African Studies Association of the United States and in 2000 was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society. His next book, to be published in Spring 2014 by the University of Wisconsin Press, is a memoir of his youth: Through the Day, Through the Night: A Flemish Belgian Boyhood and World War II.

Continue today’s blog tour and Meet these Presses:

Enjoy the rest of University Press Week! And be sure to keep a lookout for #UPWeek on Twitter.

milking—a nice eight-year-old cheddar made by

milking—a nice eight-year-old cheddar made by